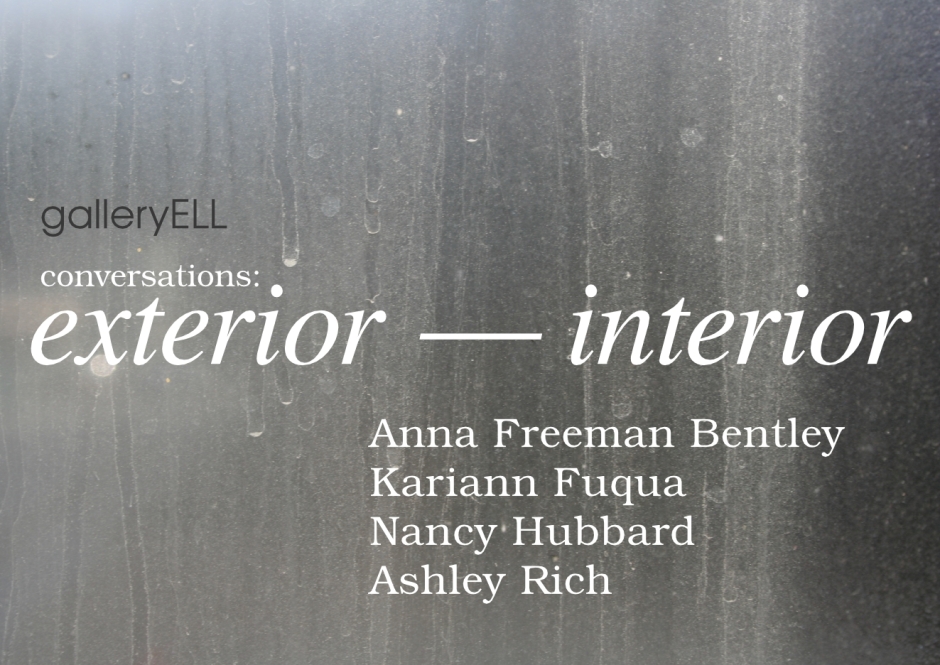

conversations: exterior—interior

08 december 2014 – 11 january 2015

curated by john ros

Anna Freeman Bentley

Kariann Fuqua

Nancy Hubbard

Ashley Rich

Inside-out. Internal-external. Anterior-posterior. Molecular::Universal. The perceptual and physical split — body, mind and spirit. When I was young I pondered similarities between the frozen forms projected through the lens of a microscope and images captured by the Hubble telescope. How do the minuscule and finite resemble the gargantuan and illimitable? This wonderment persists throughout the world, in art and in the simplest every-day surroundings, within moments that feel like dreams, some offering close-up and fleeting glimpses, and others, a life’s expanse — a whole timeline. Throughout life subtle contrasts dance around us, taunting our sense of amazement and taste for mystery. They may present as a sense of déjà vu and unravel complex emotions with a gentle nudge, allowing for vast differences in perspective. Artists create contrast accidentally and intentionally through interplay with materials, availing the viewer of tension that demands confrontation.

The photography of Sally Mann rushes to contrast and often creates mystery between interior and exterior. Pressing into our memories, Mann employs familiar language on a stage of grainy black and subtle greys. The ensuing space reveals the daunting imagery of death as closeups or landscapes waver inside and out before converging upon a final resting place somewhere in-between the life of the viewer and the stillness of the photograph. In contrast, the miraculous movement of Eadweard Muybridge’s Human figure in motion brings movement to the still image. Frame by frame, these subtly changing moments spin in an endless loop. They create contrast between inside and outs, vacillating between stillness and motion like a dream or memory. Photography may be the simplest method of tracking spacial turning from exterior to interior, as its very essence is based on the contrast of light and dark.

A rotation to interior, then untwist to exterior — these actions trigger emotion within our own viewing spaces. Neither here nor there, both interior and exterior, space exists around us as a constant — free, yet forever trapped in the eye of the beholder. Each moment becomes a new memory, a faint song, a lasting hum. Long ago Kabir wrote “The Clay Jug”,

Inside this clay jug there are canyons and pine mountains,

and the maker of canyons and pine mountains!

All seven oceans are inside, and hundreds of millions of stars.

The acid that tests gold is here, and the one who judges jewels.

And the music that comes from the strings that no one touches, and the source of all water.

If you want the truth, I will tell you the truth:

Friend, listen: the God whom I love is inside.01

I imagine a jug on a table in dark room, and a universe small enough to fit into it. The jug is made of clay from the very mountain it contains and the room floats endlessly around a star, counting time, silently aging. Every journey becomes less motivated by a rigid outline and more intriguing for the faintest possibility within.

exterior—interior, the last exhibition of the conversations series, looks to the work of Nancy Hubbard, Anna Freeman Bentley, Kariann Fuqua and Ashley Rich to unravel new mysteries transfered from the studio to the viewer and on to every space in-between.

Nancy Hubbard works on several planes. A rigorous and painstaking practice allows Hubbard to build layers — through patience. Gradual expansion of space fills more than the surface of the panel on which she works — it encompasses the air in a super-subtle time-piece. These scapes consist of tense layers that host duels between landscape and mindscape. They battle for memory and oblivion and bounce between past, present and future. Hubbard states in her own words, “My work examines the mysterious pull of time and memory by reinvigorating old world processes and integrating them with contemporary art-making methods and materials.” Through the material that is of utmost importance to Hubbard, she is as much a diligent craftswoman as she is a thoughtful storyteller as artist.

Hubbard’s stories unfold on boards within layers of plaster and pigment. Short distances may as well be enormous as their impact is exponential. Images play mostly to the land; misty, foggy, soft and silent places of peace or meditation. But these landscapes begin to shift to mindscapes and dreamscapes as they absorb the viewer. A powerful push-pull can be felt as if the viewer is caught in the breath of a single piece, forced into its lungs, then quickly exhaled. Hubbard achieves this magical trance through her own rigor and meditative practice in the studio. These pieces hover in space and time, and Hubbard politely asks the viewer to trust that they too can float somewhere in this space. More recent pieces, including Latitude 2 and Wuthering, both of which Hubbard completed in 2014, implement a vertical band on the left. By cutting through the picture plane, Hubbard creates a dual image almost like a diptych, and imposes new distance directly on an already established space, which poses the question of which came first. Though we may eventually come to a conclusion the answer is not the important part, as the acknowledgment and placement of oneself into these spaces is the true test for the viewer. We must exhale as we are exhaled from the piece, and accept the distance to which we stand in front, behind, or inside each.

With a similar discipline and patience, Anna Freeman Bentley more clearly seems to render interior spaces with layers of paint. Though there is more intention of interiors, this does not prevent the imagery, or the viewer, from shifting in and out of any particular direction. Like Hubbard, Freeman Bentley’s works are open spaces. They pulsate back and forth, from interior to even more interior and from exterior to even more exterior. The works play back and forth in the viewers imagination, prompting varied vantage points in order to take the whole picture in. Freeman Bentley eloquently refers to her paintings as, “Spaces imbued with the tension of simultaneous extremes — empty and full, interior and exterior, lost and found, surface and depth — resonate with longing. By depicting spaces that display an obvious lack or where a change of function has taken place, my painting evokes a longing that may be personal or universal; a deep human desire for permanence in a world that shows signs of decay and wear.” As Freeman Bentley examines and scrutinizes her surroundings, she invites the viewer to do the same.

The aptly titled, Orientation, 2014, runs through a series of reflections — windows and reflective surfaces — looking outside from inside, or perhaps from inside to out. Delicate handling of the surface is precise yet seemingly playful. Freeman Bentley meanders back and forth from plane to plane like a skilled ice skater, barely touching the surface, and landing every jump. Build up, 2013 has a similar sense about it, as landscape glides over landscape over cityscape within a collaged metropolis. Again, the poise with which brush dances over surface brings this viewer to his feet as he seeks the rhythm to the score of in-between spaces. These pieces ask as much of themselves as they do the viewer. We are on a ledge wanting to take another step in order to find the next place to look. That last step may hold the answer, but likely, it will throw the viewer off to a new space entirely. As we begin to trust the work in front of us, we must also begin to trust our own instincts and decisions.

Whether walking through an interior or calculating it from above, Kariann Fuqua uses architectural references to layer imagery within strata of networked space, plotting, building and laying an intricate landscape. Her earlier, more sparse works, (Vol 7 series, 2009) layer color, line and form into intricate spaces onto a prominent white page. Fuqua remarks, “By combining various architectural references, and the negative space in and around them, I am creating a newly constructed edifice. This new architectural landscape is a disorienting amalgamation of the built environment and a renegotiation of our understanding of spatial relationships … Layering imagery — whether with paint or drawing material — allows me to destabilize the viewer’s preconceived notion of place. Through my exploration of materials with paint and color, I am establishing a dialogue about place and our consistently fluctuating positions in it.” These newly-layered places become start and finish points for the viewer. One can meander throughout each piece, entering new places and discovering something extraordinary at every turn. We may clearly enter a building at one entry point, only to be left somewhere deep in the woods at the blink of an eye. This tension along with the forceful white page evokes double-takes and feelings of familiarity in the unfamiliar.

The more recent works take this process further. Leaving the white page for soft contrasting colors, Fuqua creates a thicker air for us to breath. The spaces are still open, but rather than a variant to be placed behind a corner, she moves it to a new plane directly in front of the viewer. In plain sight, Fuqua plays with a thickness (and thinness) of air on the page much like Hubbard does with the physicality of plaster. Within these newer spaces it is more difficult to distinguish interior from exterior. They may remain as one for a longer period of time, only to eventually slide back to their opposites, tumbling the viewer, as if down a grassy hill, or pushed along by a forceful gust of wind. In The in-between (GLB17), 2014, Fuqua presents us with several planes on which to stand. There is a wall of light-blue in the distance to the right, but more intriguing is the softer, lighter air-wall-space that hovers in front of that back space. The brushy-moist air feels like a fog about to lift, but the density of unseen action behind it is exhilarating. We must move to the back for further discovery. Fuqua’s spaces have become more reliant on the memory of what we have just seen, and in doing so, she has successfully dragged us out of our our cynicism of the ordinary and provided us with an air so nutritious it keeps us active within the spaces for longer periods of time. It is as if Fuqua has instilled us with patience by offering us new and impossible notions of ourselves.

Taking physical space one step further, Ashley Rich ever so subtly takes us off the page and into the world of relief sculptured paintings and drawings. This shift from two to three dimensions automatically creates a tension — a spacial shift that coincides with the conversation of interior and exterior. These structures intuitively create the space of exterior versus interior, offering only slight hints here and there as to what may be inside. Untitled, 2014 and Stickers 2, 2013 both present forms on the surface. Untitled’s less formal and rugged approach offers some space to breathe, a chance to fill in the blanks. There are more hints as to what lies within the thick plaster walls. Stickers 2, though more formal and exact, still offers possibility within space, but in a tighter, more confined way. The impressions laid on the striped surface create soft channels and crevices. I am again reminded of the thin plaster surfaces of Nancy Hubbard’s work, but Rich brings these layers to a new a determined actual and tangible depth. The vales and inverted summits hold endless minutiae. We become specks of dust on the surface. Each imprint falls, as if placed systemically, connected in some varied and random way — a map through the material and quite possibly onto the other side.

Rich’s focus in the studio deals directly with tension between surface and space. He states, “The visual stimulation that resides on the works’ physical facade emerges from a superficial detachment to its influences in modernist architecture and ornamentation … [T]he work aims to focus on the point where the two-dimensional transforms into the three-dimensional. These elements develop into an interplay between the rational and the intuitive helping to reflect a fragmented vision of urban abstraction.” This very interplay keeps the objects vibrating. As we move from space to space, each piece moves with us, embarking on a long journey through history and delving into a vast future of discovery and promise. Rich takes our hands while presenting familiar materials in the most unfamiliar ways. He managed to transform material much like he transforms the spaces in which the material resides. And he does not stop there. Additional interaction happens as a function of the physical placement of objects within a space and in relation to one another. Rich too is a storyteller, leading us from chapter to chapter of an engrossing tale. Only after some time, perhaps even after we leave the work, we discover we are the protagonists.

The artists in this exhibit deal with materials and space as a way of activating the physical, mental and emotional spaces of each viewer. As we approach, we find ourselves floating between places: interior, exterior; near, far; in air, under water; in past, in future. The constant push-pull tension these artists create bring all moments to pause and ask the viewer to contribute to the discussion. As viewers, we contribute by engaging with the work and with ourselves. We are lucky to be surrounded by the generosity of these four artists. They host conversation through their practices. Art does not stop once the piece is hung on the wall, or sold on the secondary market for a profit. Art is about persistence and continuation. Without the brave practices of artists and contributions of viewers, we might as well be living in a vacuum.

Perhaps Agnes Martin said it best,

“My interest is in experience that is wordless and silent, and in the fact that this experience can be expressed for me in art work which is also wordless and silent. It is really wonderful to contemplate the experience and the works …

[W]ith regard to the inner life of each of us it may be of great significance. If we can perceive ourselves in the work — not the work but ourselves when viewing the work then the work is important. If we can know our response, see in ourselves what we have received from a work, that is the way to understanding of truth and all beauty.

We cannot understand the process of life — that is everything that happens to everyone. But we can know the truth by seeing ourselves, by seeing the response to the work in ourselves.”02

As viewers, we absorb each new art experience and make it our own. We do this not to impose our own beliefs onto a piece, but to truly converse with a piece and find ourselves within it. As David Ignow wrote, “I should be content / to look at a mountain / for what it is / and not as a comment / on my life.”03 This is what Agnes Martin implies: to truly know ourselves is to truly know our world, for we provide the lenses through which we may apprehend the world. To know ourselves, we must know our world. The only way to do that is to shift our perspectives, thus increasing our awareness of our surroundings, and ultimately, of ourselves. Outside and in, we are active and participatory. In this activity we must remain honest and open.

Exhibition gallery: click on an image below to view the exhibition.

notes:

01. Kabir, version by Robert Bly: Robert Bly, ed. “THE CLAY JUG.” /News of the Universe/. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. 1980. p.272

02. Von Dieter Schwarz, Herausgegeben, ed. Agnes Martin Writings. Ostfildern: Cantz, 1991. print., page 89.

03. David Ignow quote | Robert Bly, ed. /News of the Universe/. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. 1980. p.123

other exhibits in this series:

13 october – 09 november 2014: conversations: SPACE&time

10 november – 07 december 2014: conversations: /HOME/

conversations: explained.

This 3-part series of exhibitions is an investigation into specific ideas within artists’ practices and how those paths unfold into the broader conversation for the audience. Each exhibit will bring artists from the US and the UK together to begin discussions into slightly obscure ideas that resonate throughout broader, less-obvious themes. SPACE&time: a look into how space and time may shift and how our own perspectives of each affect our experiences; /HOME/, a discussion on what it means to be “home” and how artists work to create that experience; and exterior—interior, how the morphing of space can allow it to become both interior and exterior at the same time.

The studio is the starting point for all of these conversations. When one experiences an artist’s raw, unedited practice, you can begin to better understand the depth of research involved. Not all work is a success, nor should it be. Of those “horrible works”, our instinct is to put it away, to bury it, destroy it. At Brooklyn College, Archie Rand always said to keep that piece hung in the studio and to stare at it, to communicate with it, to allow for it to loom over our practice a while. He reassured us that it was a pure and honest expression from our gut and eventually it would reveal its purpose. In a similar vain, Kirsten Nash recently curated the exhibit, Pleasure & Pain, for galleryELL.

From studio to exhibition, this series aims to create a venue for honest creativity and a discussion of possibilities.