Figur|e|ation.

20 April – 05 July 2015

curated by john ros

Joel Bacon

Fiona Birnie & Kevin Broughton

William Bock

Bethe Bronson

Vicki Cooke

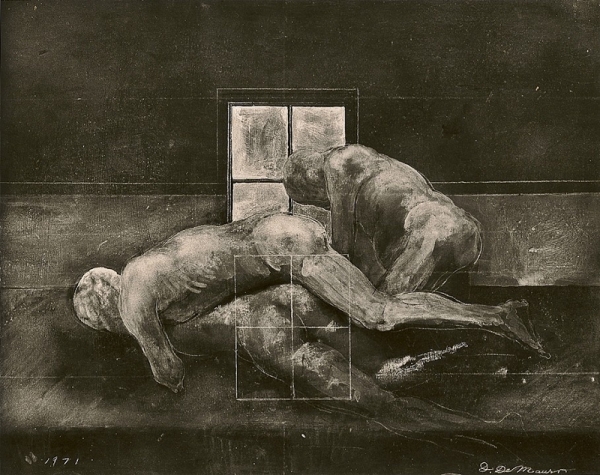

Don De Mauro

Jenny Gibson

Jay Rechsteiner

Irini Urania Politi

Barbara Walker

INTRODUCTION

The human figure is indeed an intricate and difficult subject to tackle as an artist. It is loaded and familiar and can easily fall into cliché, or worse, bore. As viewers, we are almost too connected to the subject matter to really pull back enough to be able to see the bigger picture presented. In reality then, we often find ourselves disconnected from the work by our personal existence as a figure ourselves. And the opposite is also true: when we become too invested in an artwork and overlay our experiences too much, it reflects our prejudices and preconceptions. The figure, thus, in our current social and political landscape, plays an ever important role in our cultural experiences and social expressions. To truly appreciate the range of contemporary figurative artwork, we have no choice but to bring our experiences with us and allow room for growth in our reading of the work.

We are connected to this world in every way through the figure. It is hard to escape the confinements of our skin — our culture — our atmosphere. We humanize everything from our pets to the spaces we inhabit and the objects we use. In order to relate to abstractions, we often try to find faces or familiar objects in them. We are even more attracted to people who look similar to ourselves.

As we move throughout our day, many actions become automatic. Technology pushes and tugs us into one direction or the next: we are subject to a constant deluge of information and access by others. We are becoming less and less able to be with ourselves and our thoughts. That is not to say technology is inherently bad, we just have to learn to develop a new sense of awareness around it as we continue to struggle through our existence as human beings. Beyond the invisible motion of the technological energy all around us, we also are in constant movement. Our bodies, minds and souls are catching up to all this motion.

Figur|e|ation. is a glimpse into current figurative works. Artists tackle the subject with different materials, modes and intentions. This exhibition looks into that which is truly human — in a way that connects us to the fact that we are the human figure. We cannot escape this reality — at least for now. Reminding ourselves of that represents a starting point of appreciating our abilities and inabilities within our own figure. In awareness and through accepting the limits that exist — from skin to ability — from border and beyond — we can begin to experience more of the world, and ultimately, ourselves.

OUR EXISTENTIAL MOMENT

The existentialists believed in the sole authenticity of the individual among the countless absurdities that surround us. This “authenticity” is challenged countless times a day in our contemporary moment. Though this is not new, it seems we are challenged more often and to a wider degree with vast information at our fingertips and the growth of global (corporate) culture. Each and every one of us deals with this in different ways. The more we look around at the rest of the world, perhaps we can see the triviality and absurdity to our plight. Perhaps the most absurd element is that we are all just brought into this existence: No one can choose which ethnic, social or economic group to belong to. We are just placed and asked to exist.

Gregor Samsa, the protagonist of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, wakes up one day transformed into a “monstrous vermin.” Once a traveling salesman, Samsa is the perfect specimen in search of authenticity in a space (and body) of struggle and pain. Whether he prospers or perishes in this new state, he has the knowledge of a life before — as a human.

“Groping clumsily with his antennae, which he was only now beginning to appreciate, he slowly dragged himself toward the door to see what had been happening there. His left side felt like one single long, unpleasantly tautening scar, and he actually had a limp on this two rows of legs. Besides, one little leg had been seriously injured . . . and dragged along lifelessly.” 01

The tension of pain and loneliness can be felt in Samsa’s attempts at movement. And like his experience, our own movements through life can be restricted, difficult and unpleasant.

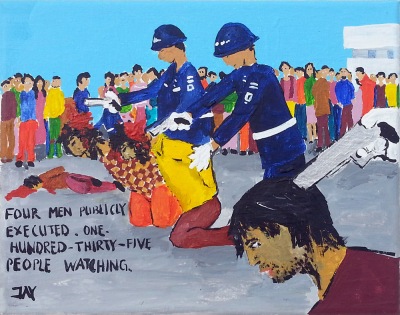

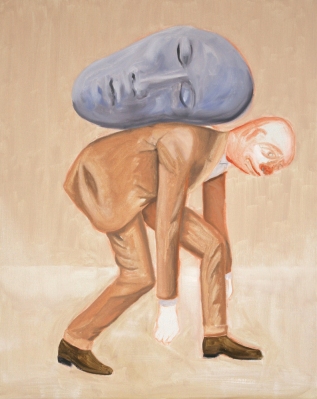

Jay Rechsteiner’s Bad Paintings (2013) brings the horrors of human culpability front and center. We don’t have to look too far to see the atrocities within our communities. Turn on the news, take an extended walk through familiar streets. Sadness and pain are everywhere. Rechsteiner states that his “main interest [is] in the underlying structure of things [and how] his artworks directly respond to the surrounding environment and . . . everyday experiences.” We so often look for beauty in everything. Why not accept the ugliness of misery? Confront it and learn how to deal with it? Rechsteiner wrestles with these ideas in his studio and asks the same of his veiwer. He wishes to “demonstrate how life extends beyond [our] own subjective limits,” to tell “a story about the effects of global cultural interaction,” and “the binaries we continually reconstruct between Self and Other, between our own ‘cannibal’ and ‘civilized’ selves.”Don De Mauro deals with similar issues, but in a broader and more psychological landscape. An existentialist at heart, De Mauro fumbles with his own humanity in the constant of absurdity. He states: “This existential perspective, grounded by its opposition to all inherited forms of transcendence was consistent with and key to my own existential formation. Concepts of immanence, singularity, multiplicity and becoming, could and would ground my aesthetic and social choices. It interested me that ‘art’ was a socially functional strategy for the existential impulse.” The figurative and psychological go hand in hand. De Mauro’s persistence can be experienced throughout his oeuvre. He is dedicated to the transfer of knowledge and the power of language. “Art is language, and the body is the site of language. . . . [T]he body is by its existential nature nomadic and migrates to the figural. The term figural wants to acknowledge singularity, multiplicity, form, boundaries and becoming. Art is equally anatomical and political, personal and social. The body is the site of conception and sensation. Art . . . mediates and interprets through line, shape, plane, tone and color, the internal and external intensities of boundaries and their entanglements.” De Mauro consistently researches the body’s ability to convey language: From full-body studies to singular elements such as Privilege (1992) or Untitled (2002), he brings focus to individual body parts as if stressing the strength of the individual psyche within the parameters of the body.

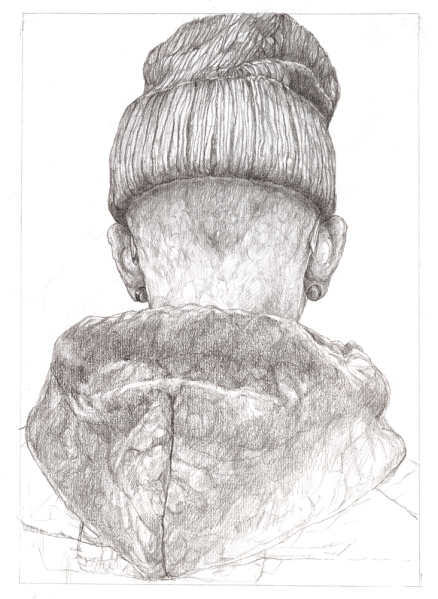

Barbara Walker takes these same ideas of the individual within a social and political context and relates them to the specifics of clothing. She presents the viewer with an interesting dilema — one we are all faced with every day — judging identity based on limited information. In the case of Walker’s series Show and Tell (2008), she shows us the back of a figure. We are forced to react based on the clothing, stature, and body language of the figure in front of us. Walker has chosen to represent clothing as a status symbol and “[b]y obscuring [the individual’s] identity . . . invites [us] to scrutinise the ‘information’ available — clothing, hair and jewellery — in order to complete the portrait” and to “investigate expressions of individuality, conformity and stereotyping.” She is particularly interested in consumerism, fashion and media. Walker asks simply: “How far are fashion and consumerism responsible for providing the styles that individuals desire? Do individuals take the lead on how they choose to look while fashion and commercialism follow? And what role does the media play informing public opinion?”

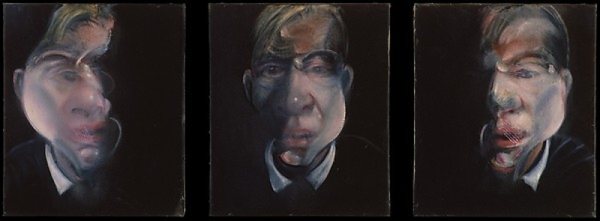

Each of these artists takes the figure as a starting point to a much broader social message. Sometimes these images may not be the easiest to observe and understand. Francis Bacon’s morphing figures and spaces come to mind. They match the gripping, painful transformations Gregor Samsa experienced in the confinement of his dark room. Though gnarled and torn, Bacon’s figures arouse with intimacy and gruesomeness, for the figures are just like us, in lust of balance, beauty, love — normalcy within their own physicalness.

“[Francis] Bacon could not conceive of a ‘great’ art divorced from reality, from the concrete particulars of human existence in an alarmingly hostile world whose inhabitants find themselves increasingly alienated and disoriented. Insisting on the need for art to confront the real, he was firmly convinced that only an art of this kind could elicit an emotional response from the beholder – and in his view, only an art that appealed to the emotions could qualify as ‘great’.” 02

Ideas of the identity we receive versus our perceived identity are symptomatic of our culture. As we move through our spaces from moment to moment, it is important to understand the many views by which one single event can be observed. From atrocities in plain sight, to our deeper inner philosophies, to our prejudices and reactions — perceived observations make up our daily moments and ask much of us. We must have the patience and confidence to deal with them openly. Movement is key. Each day presents something new. A new place, a new element — perhaps one day we wake up a “monstrous vermin” . . . perhaps we already have?

OUR EXISTENTIAL MOMENT Gallery: click on an image below to view this section as a slide show.

THE PSYCHE OF MOTION / THE MORPHING OF THE EVERYDAY

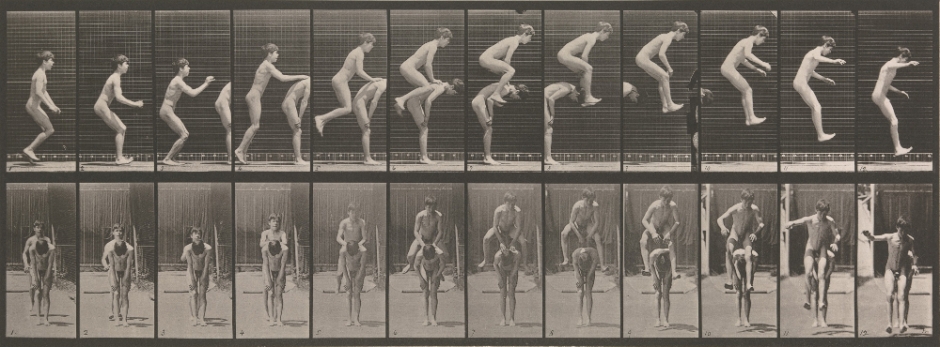

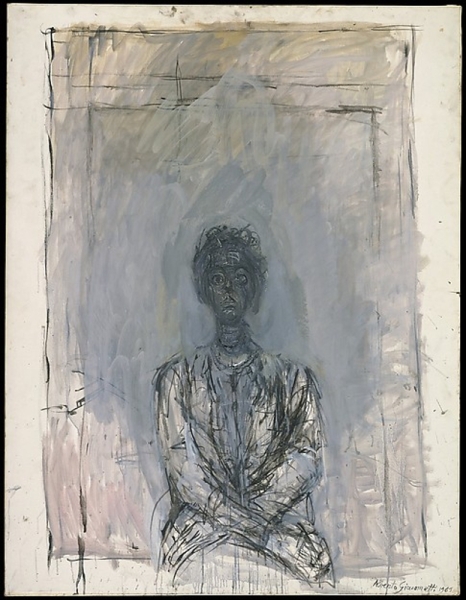

The still figure in motion. Constant. Whether in a freeze-frame moving image, still-by-still, or in humming, hovering, vibrating motion, the figure is a continual source of interaction and discovery. We can go back to Eadweard Muybridge or fast-forward to Alberto Giacometti. Both of these artists studied the figure in motion — and both succeeded in very different ways. Muybridge brought us the intermittent movements of human locomotion. His photographic studies have been used countless times by other artists fascinated with the human form and its movement.

Giacometti places us in motion in a very different way. We are physically still. We are motionless as we view the portrait, like the sitter, but we somehow sense movement. He manages to breathe life into the sitter by capturing the movement of air around her. In some ways he seems more interested in the spaces between the sitter’s skin and the walls of the room, rather than in the actual model. In this peculiar precision, he is able to create a more effective figure — one with more life and honesty. Muybridge and Giacometti make us aware of the figure by way of the time and space the figure occupies. They remind us that the space we ourselves occupy affects our perceptions; that our own actions within that space contain the magic of possibility and the mysteries revealed in failure.

Giacometti, Annette (1961). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Through arduous layering of the seemingly same image, Joel Bacon is able to capture endless variations. Like a fingerprint or handwriting, each replicated figure represents a unique moment in the space of perpetual moments. The slight changes and shifts alert the viewer of perceptual shifts that bring the whole piece to life. By building these pieces, as if using bricks and mortar, Bacon forms a foundation on which to view variations within ourselves and differences in each other. Within the subtle variations, Bacon also comments on possibility within the formal constraints of conformity and unity, and on the anxiety of mutation and evolution. To break free and become a singular element — seeking the divide versus promoting it. Bacon toes the line, moving in and out of physical and metaphysical happenings.

With similar subtlety, Irini Urania Politi plays with motion within interiors. She captures the mundane and the simple, creating an air of mystery and silence. We are drawn into these events as onlookers. Not voyeurs, we almost become characters in the scene — like the objects in the room — for we seem involved, not just a curious eavesdroppers. These images represent basic and sometimes involuntary tasks that take up so much of our time. Politi reminds us of these moments. She elevates them. There is a play of color and light as well as staging that seems effective overall. Politi aims to give a “psychological experience” to the viewer. She states, “Challenging expectations is part of this game to force the viewer to never quite feel comfortable with the image, yet finding it visually interesting and seductive at the same time.”

Politi’s images are reminiscent of the mundanity of Camus’s character Meursault in The Stranger:

From mundane to bizarre: the artist duo Fiona Birnie and Kevin Broughton come to motion with paint, collage and satire. These pieces morph and mutate. In The Kiss (2014) and Head (2015), we imagine life from a different perspective. The pulse comes alive as canvas and paint become skin. We can feel the tightness and discomfort of the subjects, yet they seem to be enjoying themselves. Birnie and Broughton represent satire at its best in these morphing moments through the disturbing realization that they are not all that farfetched. These images become too close for comfort in many ways as we realize they are bits and pieces of the world stretched out before us. Their statement contends, “With the vast quantity of data available it becomes impossible to process, leaving the individual to take fragmented information from the media/internet, assembling ill-fitting parts to construct their own often distorted vision of the world. . . . History, myth, news, gossip, personal experience and emotions connect to create a fragile and surreal concept of reality.”“After lunch I was a little bored and I wandered around the apartment. It was just the right size when Maman was here. Now it’s too big for me, and I’ve had to move the dining room table into my bedroom. I live in just one room now, with some saggy straw chairs, a wardrobe whose mirror has gone yellow, a dressing table, and a brass bed. I’ve let the rest go. A little later, just for something to do, I picked up an old newspaper and read it. I cut out an advertisement for Kruschen Salts and stuck it in an old notebook where I put things from the papers that interest me. I also washed my hands, and then went out onto the balcony” 03

Jenny Gibson plays with the motion of the everyday as seen through the eye of the consumer. What could be more apt (especially to a Western onlooker) than the overconsumption of unnecessary material, or the gluttonous consumption of endless variety to represent the everyday. Gibson is playing with this material as a way of confronting the issue at its heart — by further contributing to the excessive consumption. The color and texture within these photographs are appealing, yet the imagery is disturbing. We are challenged with the understanding that we are looking at ourselves. Gibson agrees, “I’m very interested in the voracious way we consume in this country. . . . I look for rough-edged, joyful beauty — always on the brink of something unpleasant.” This movement may be all too familiar to some, unpleasant to others. Gibson is creating a space for dialogue — first and foremost, a dialogue with ourselves, but then we have to begin to ask ourselves, what are we leaving behind and at what cost?

THE PSYCHE OF MOTION / THE MORPHING OF THE EVERYDAY Gallery: click on an image below to view this section as a slide show.

REMNANT

What remains? We have struggled with this question throughout our lives wondering, most commonly, what happens after we die. The photographer Sally Mann writes,

“When the land subsumes the dead, they become the rich body of earth, the dark matter of creation. As I walk the fields of this farm, beneath my feet shift the bones of incalculable bodies; death is the sculptor of the ravishing landscape, the terrible mother, the damp creator of life, by whom we are one day devoured” 04

The passage of time is constant but what fragments of ourselves do we leave behind every day? How do we leave our mark when we end a conversation or participate in an experience? What energy or example do we leave and what is its environmental, social, spiritual impact? Like similar questions relating to death, these questions about what we leave behind in life may seem easier to locate, but even harder to discuss. What do we leave behind?

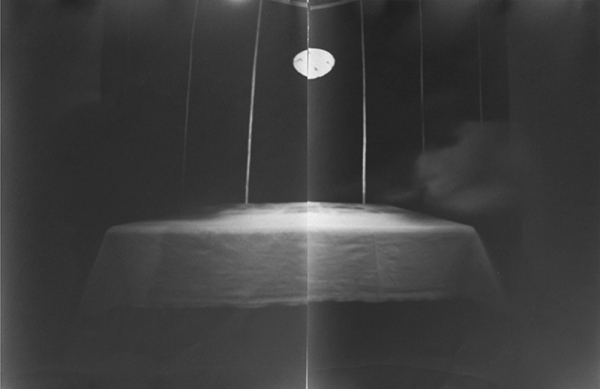

William Bock creates extended moments. In his process of illustrating duration, he stretches time, looking to pinpoint the moment of synthesis or action — his vast images are like looking through a pinhole to reveal a massive scene with endless possibility. In fact, Bock’s Meeting Series (2013) is developed with extended exposures through a pinhole camera. There is a sense of simplicity here, like the stage he has set. We wait in anticipation for our turn to contribute to the conversation. Bock’s Surname Series (2015) was created compressing over two hundred digital images of a man performing a repeated action. Again, we find we are stuck somewhere in-between, in the shadow of moments. In the remains of time. Bock compresses past, present and future. In developing his imagery he begins to map a clear language for timelessness.

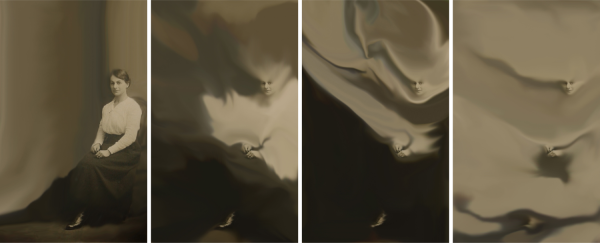

Transforming time, Bethe Bronson’s images meander in space and float away before our very eyes. Her soft images, created from stills of the video All Consuming (2014) focus on the fleeting moment and the texture of time. It is as if you can reach out and touch the air. The velvet, amorphous current takes hold to reveal a lifetime in mere seconds. Though the shifts do not necessarily age, one cannot help but feel time passing at a rate that seems inescapable. Bronson has said of her work, “Conceptually as well as concretely, I’m concerned with what’s not there, what we don’t see and how it affects what we do see.” She has allowed us to see time and air in a way that is so tangible we may touch it. As we watch the video All Consuming (2014), we await the inevitable disappearance of the figure. Surprisingly it does not happen. We are left with a gaze and a hand.

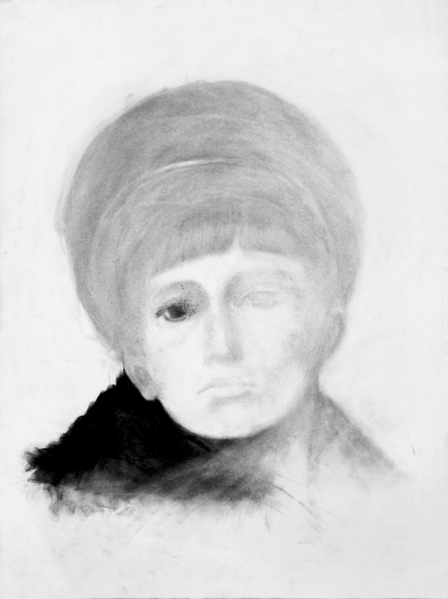

As if picking up where Bronson’s All Consuming (2014) leaves off, Vicki Cooke brings historical figures into the present moment. She accomplishes this time shift in her body of work that acknowledges artists left out of history and gives them prominence; then she reverses time by erasing or sanding their visages away. Cooke’s method both recognizes these women for their achievements and brings their omission from history to light. We can almost smell the rubber from the eraser, or hear the soft abrasion of the sandpaper on the drawing. Dust and erasure bits fill the air. While reminding us of these important women, she also reminds us of their frailty. We are invited to this moment in time and are shown a great mystery of memory and oblivion. Cooke states, “I have been working on revealing the images of women so that they can peer out of the past and into the present.”

Bock, Bronson and Cooke all confront time and elements of self within their investigative research. Their moments are placed in front of us to hold onto the here and now. Whether as individuals we live more actively in the past, present or future, these artists present us with time as a continuum — a notion that time is not only constant but amorphous. We have the ability to move throughout that continuum, we just have to be aware of it.

From Emily Dickinson’s poem 624 (c. 1862)

Forever – is composed of Nows –

’Tis not a different time –

Except for Infiniteness –

And Latitude of Home –From this – experienced Here –

Remove the Dates – to These –

Let Months dissolve in further Months –

And Years – exhale in Years –Without Debate – or Pause –

Or Celebrated Days –

No different Our Years would be

From Anno Domini’s – 05

REMNANT Gallery: click on an image below to view this section as a slide show.

CONCLUSION: THE BEGINNING

This seems more like a starting point. An introduction. Experiences are often bookended, but they are in an endless loop of activity that surrounds us all. Each and every moment is existing right now — over seven billion times over. As that may be too much to grasp, we can start small. Don De Mauro may have stated it best about his own work (but it’s appropriate for this whole exhibition):

“In the end these works — these things presented and represented — need to be made well enough and then nurtured, so that the work speaks for itself. Visual art wants to give physical matter its own sensate logic — a voice.”

Often the overly philosophical conversations of our own existential crises or the exacerbated human condition evade us and allow the conversation to float in oblivion. These ethereal conversations are so important but require action on the ground too.

The figure is inherently political. Our bodies are equal rights, incarceration, inequality, abortion, rape, human trafficking, torture, war — the list is endless. It is our responsibility to be human, in our figure, and to create a world that is free and open for all our similarities and differences. It seems we often want to focus more on our similarities as a way of bringing us closer to others. However, the more we aim to find our similarities, the more divisive we make the world. Perhaps the more we are surrounded by “like-minded” people, the less tolerant we become of our differences. Rather than focus on our similarities, how much more interesting would it be to negotiate our differences? How can we aim for a space that promotes a truly free and open society for everyone?

01. Kafka, Franz. The Metamorphosis. New York: Bantam Books,1986. Print.

02. Schmied, Wieland. Francis Bacon: Commitment and Conflict. Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1996. Print.

03. Camus, Albert. The Stranger. New York: Vintage International, 1989. Print

04. Mann, Sally. What Remains. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2003. Print.

05. Johnson, Thomas H., ed. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960. Print.